Paleolithic Period

During the Paleolithic period (c. 500,000-17,000 BCE), the inhabitants of Jordan hunted wild animals and foraged for wild plants, probably following the movement of animals seeking pasture and living near sources of water.

Neolithic Period

During the Neolithic period (c. 8500-4500 BCE), or New Stone Age, three great shifts took place in the land now known as Jordan. First, people settled down to community life in small villages. The second basic shift in settlement patterns was prompted by the changing weather of the eastern desert. The most significant development of the late Neolithic period, from about 5500-4500 BCE, was the making of pottery. The largest Neolithic site in Jordan is at Ein Ghazal in Amman. It consists of a large number of buildings, which were divided into three distinct districts.

Chalcolithic Period

During the Chalcolithic period (c. 4500-3200 BCE), copper was smelted for the first time. It was put to use in making axes, arrowheads and hooks, although flint tools also continued to be used for a long time. Chalcolithic man relied less on hunting than in Neolithic times, instead focusing more on sheep and goat-breeding and the cultivation of wheat, barley, dates, olives and lentils.

Early Bronze Age

By about 3200 BCE, Jordan had developed a relatively urban character. Many settlements were established during the Early Bronze Age (c. 3200-1950 BCE) in various parts of Jordan, both in the Jordan Valley and on higher ground. Many of the villages built during this time included defensive fortifications to protect the inhabitants from marauding nomadic tribes still inhabiting the region. Water was channeled from one place to another and precautions were even taken against earthquakes and floods.

Middle Bronze Age

During the Middle Bronze Age (c. 1950-1550 BCE), people began to move around the Middle East to a far greater extent than before. Trading continued to develop between Egypt, Syria, Arabia, Palestine and Jordan, resulting in the refinement and spread of civilization and technology. The creation of bronze out of copper and tin resulted in harder and more durable axes, knives and other tools and weapons. It seems that during this period large and distinct communities arose in parts of northern and central Jordan, while the south was populated by a nomadic, Bedouin-type of people known as the Shasu.

Late Bronze Age

The Late Bronze Age was brought to a mysterious end around 1200 BCE, with the collapse of many of the Near Eastern and Mediterranean kingdoms. The main cities of Mycenaean Greece and Cyprus, of the Hittites in Anatolia, and of Late Bronze Age Syria, Palestine and Jordan were destroyed. It is thought that this destruction was wrought by the "Sea Peoples" marauders from the Aegean and Anatolia who were eventually defeated by the Egyptian pharoahs Merenptah and Rameses III. One group of Sea Peoples were the Philistines, who settled on the southern coast of Palestine and gave the area its name.

The Old Testament Kingdoms of Jordan

The Iron Age (c. 1200-332 BCE) saw the development and consolidation of three new kingdoms in Jordan: Edom in the south, Moab in central Jordan, and Ammon in the northern mountain areas. To the north in Syria, the Aramaeans made their capital in Damascus. This period saw a shift in the level of power from individual “city-states” to larger kingdoms. One possible reason for the growth of these local kingdoms was the growing importance of the trade route from Arabia, which carried gold, spices and precious metals through Amman and Damascus up to northern Syria.

The Hellenistic Period

Although the influence of Greek culture had been felt in Jordan previously, Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Middle East and Central Asia firmly consolidated the influence of Hellenistic culture. The Greeks founded new cities in Jordan, such as Umm Qais (known as Gadara) and renamed others, such as Amman (renamed from Rabbath-Ammon to Philadelphia) and Jerash (renamed from Garshu to Antioch, and later to Gerasa). Many of the sites built during this period were later redesigned and reconstructed during the Roman, Byzantine and Islamic eras, so only fragments remain from the Hellenistic period. Greek was established as the official language, although Aramaic remained the primary spoken language of ordinary people. Alexander died soon after establishing his empire, and his generals subsequently struggled over control of the Near East for more than two decades. Eventually, the Ptolemies consolidated their power in Egypt and ruled Jordan from 301-198 BCE. The Seleucids, who were based in Syria, ruled Jordan from 198-63 BCE.

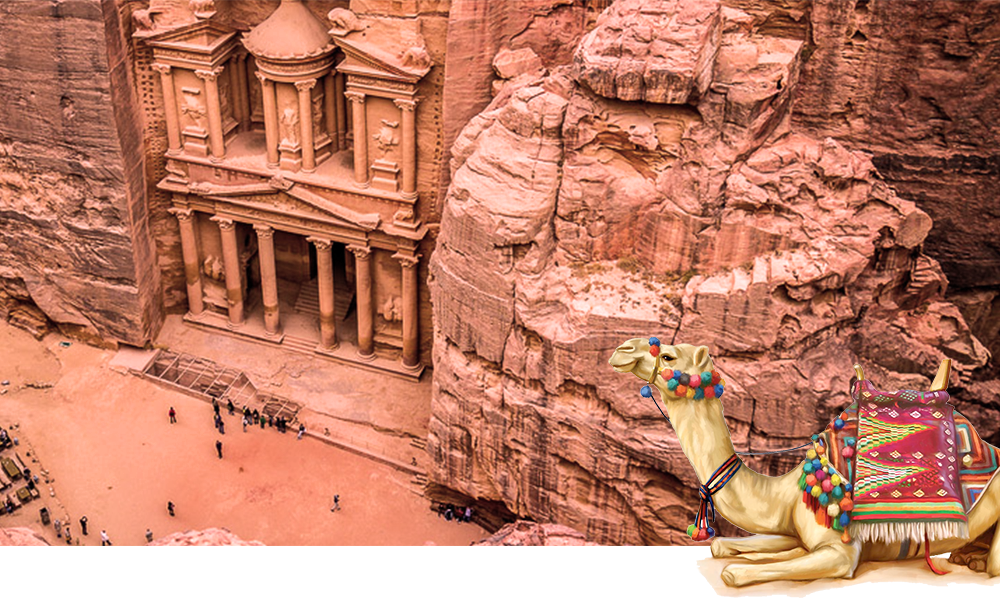

The Mysterious Nabateans

Before Alexander’s conquest, a thriving new civilization had emerged in southern Jordan. It appears that a nomadic tribe known as the Nabateans began migrating gradually from Arabia during the sixth century BCE. Over time, they abandoned their nomadic ways and settled in a number of places in southern Jordan, the Naqab desert in Palestine, and in northern Arabia. Their capital city was the legendary Petra, Jordan’s most famous tourist attraction. Although Petra was inhabited by the Edomites before the arrival of the Nabateans, the latter carved grandiose buildings, temples and tombs out of solid sandstone rock. They also constructed a wall to fortify the city, although Petra was almost naturally defended by the surrounding sandstone mountains. Building an empire in the arid desert also forced the Nabateans to excel in water conservation. They were highly skilled water engineers, and irrigated their land with an extensive system of dams, canals and reservoirs.

The Age of Rome

Pompey’s conquest of Jordan, Syria and Palestine in 63 BCE inaugurated a period of Roman control which would last four centuries. In northern Jordan, the Greek cities of Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa (Jerash), Gadara (Umm Qais), Pella and Arbila (Irbid) joined with other cities in Palestine and southern Syria to form the Decapolis League, a fabled confederation linked by bonds of economic and cultural interest. Of these, Jerash appears to have been the most splendid. It was one of the greatest provincial cities in Rome’s empire, and was honored by a visit of the Emperor Hadrian himself in 130 CE. In southern Jordan, the Kingdom of Nabatea retained its independence until 106 CE, when Emperor Trajan’s forces took control of the region.

Christendom and the Byzantines

The Byzantine period dates from the year 324 CE, when the Emperor Constantine I founded Constantinople (Istanbul) as the capital of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire. Constantine converted to the growing religion of Christianity in 333 CE. In Jordan, however, the Christian community had developed much earlier: Pella had been a center of refuge for Christians fleeing persecution in Rome during the first century CE. During the Byzantine period, a great deal of construction took place throughout Jordan. All of the major cities of the Roman era continued to flourish, and the regional population boomed. As Christianity gradually became the accepted religion of the area in the fourth century, churches and chapels began to sprout up across Jordan.

The Islamic Periods and the Crusades

The Byzantines’ preoccupation with the Sassanians diverted their attention away from what was happening in the Arabian desert. For countless years marauding Bedouin tribesmen had periodically staged raids to the north. What was new, however, was that the Arabs who swept northward on horse and camel-back were now united by a common faith, that of Islam. After hearing the call of God, the Prophet Muhammad, Praise Be Unto Him (PBUH), first tried to convert the people of his home, Mecca. When the Meccans threatened him and his followers, they journeyed to the neighboring town of Medina in the year 622 CE. This migration, known as the Hijra, marks the beginning of the Muslim calendar. Eight years later, the Prophet returned to Mecca to convert its people to Islam. From then on, the new faith spread rapidly throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

Umayyad Empire

The Muslims wasted no time in taking Damascus, and in 661 CE proclaimed it the capital of the Umayyad Empire. Jordan prospered during the Umayyad period (661-750 CE) due to its proximity to the capital city of Damascus. Its strategic geographic position also made it an important thoroughfare for pilgrims venturing to the holy Muslim sites in Arabia. As Islam spread, the Arabic language gradually came to supplant Greek as the main language. Christianity was still widely practiced through the eighth century. The Umayyads were comfortable and at home in the desert. They felt little need for the Roman fortifications which guarded trading routes, and subsequently allowed them to fall into disrepair. However, they left an enduring legacy to bear testimony to their love of hunting, sport and leisure.

Abbasids

A powerful earthquake rocked Jordan in 747 CE, destroying many buildings and perhaps contributing to the defeat of the Umayyads by the Abbasids three years later. The Abbasids established their capital in Baghdad, leaving Jordan a provincial backwater far from the center of the empire. The Desert Castles were abandoned, and Jordan now suffered more from benign neglect than from the attentions of invading armies. However, recent excavations have shown that the population of Jordan continued to increase, at least until the beginning of the 9th century CE.

Fatimids

In 969 CE, the Fatimids of Egypt took control of Jordan and struggled over it with various Syrian factions for about two centuries. At the beginning of the 12th century CE, however, a new campaign was launched which would once again place Jordan at the center of a historical struggle. The impetus for the Crusades came from a plea for help from the Emperor of Constantinople, Alexius, who in 1095 reported to his Christian European brothers that his city, the last bastion of Byzantine Christendom, was under imminent threat of attack by the Muslim Turks. The prospect of such a severe defeat prompted Pope Urban II to muster support for Constantinople as well as for the retaking of Jerusalem.

Ayyubid and Mamluks

Salah Eddin founded the Ayyubid dynasty, which ruled much of Syria, Egypt and Jordan for the next eighty years. In the year 1258 CE, an invasion of Mongols swept across much of the Near East. The marauding invaders were eventually turned back in 1260 CE by the Mamluk Sultan Baybars, who fought a successful battle at Ein Jalut. The Mamluks, who were from Central Asia and the Caucasus, seized power and ruled Egypt and later Jordan and Syria from their capital at Cairo.

The Ottoman Empire |

The four centuries of Ottoman rule (1516-1918 CE) were a period of general stagnation in Jordan. The Ottomans were primarily interested in Jordan in terms of its importance to the pilgrimage route to Mecca al-Mukarrama. They built a series of square fortresses—at Qasr al-Dab’a, Qasr Qatraneh, and Qal’at Hasa—to protect pilgrims from the desert tribes and to provide them with sources of food and water. However, the Ottoman administration was weak and could not effectively control the Bedouin tribes. Over the course of Ottoman rule, many towns and villages were abandoned, agriculture declined, and families and tribes moved frequently from one village to another. The Bedouins, however, remained masters of the desert, continuing to live much as they had for hundreds of years.

The Great Arab Revolt

Much of the trauma and dislocation suffered by the peoples of the Middle East during the 20th century can be traced to the events surrounding World War I. During the conflict, the Ottoman Empire sided with the Central Powers against the Allies. Seeing an opportunity to liberate Arab lands from Turkish oppression, and trusting the honor of British officials who promised their support for a unified kingdom for the Arab lands, Sharif Hussein bin Ali, Emir of Mecca and King of the Arabs (and great grandfather of King Hussein), launched the Great Arab Revolt. After the conclusion of the war, however, the victors reneged on their promises to the Arabs, carving from the dismembered Ottoman lands a patchwork system of mandates and protectorates. While the colonial powers denied the Arabs their promised single unified Arab state, it is nevertheless testimony to the effectiveness of the Great Arab Revolt that the Hashemite family was able to secure Arab rule over Transjordan, Iraq and Arabia.

The Making of Transjordan

Although the Sykes-Picot Agreement was modified considerably in practice, it established a framework for the mandate system which was imposed in the years following the war. Near the end of 1918, the Hashemite Emir Faisal set up an independent government in Damascus. However, his demand at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference for independence throughout the Arab world was met with rejection from the colonial powers. In 1920 and for a brief duration, Faisal assumed the throne of Syria and his elder brother Abdullah was offered the crown of Iraq by the Iraqi representatives. However, the British government ignored the will of the Iraqi people. Shortly afterward, the newly-founded League of Nations awarded Britain the mandates over Transjordan, Palestine and Iraq. France was given the mandate over Syria and Lebanon, but had to take Damascus by force, removing King Faisal from the throne to which he had been elected by the General Syrian Congress in 1920.

The Tragedy of Palestine

The Balfour Declaration’s commitment to a Jewish national home in the British mandate of Palestine soon came back to haunt Britain and the Arabs. Arabs were outraged by the implication that they were the intruders in Palestine, when in fact at the end of World War II they accounted for about 90% of the population. While Jewish immigration to Palestine in the 1920’s caused little alarm, the situation escalated markedly with the rise of Nazi persecution in Europe. Large numbers of European Jews flocked to Palestine, inflaming nationalist passions among all Arabs, who feared the creation of a Jewish state in which they would be the losers. Palestinian resistance erupted into a full-scale revolt which lasted from 1936-39. This revolt, which in some respects resembled the intifada of the late 1980s, was the first major outbreak of Palestinian-Zionist hostilities.

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Prior to the UN General Assembly’s November 1947 decision to partition Palestine, King Abdullah had proposed sending the Arab Legion to defend the Arabs of Palestine. Reacting to the passing of the partition plan, he announced Jordan’s readiness to deploy the full force of the Arab Legion in Palestine. An Arab League meeting held in Amman two days before the expiration of the British mandate concluded that Arab countries would send troops to Palestine to join forces with Jordan’s army.

The Disaster of 1967

In early 1963, Israel announced its intention to divert part of the Jordan River waters to irrigate the Naqab Desert (also known as the Negev Desert). In response, Arab leaders decided at a 1964 Cairo summit to reduce the flow of water into Lake Tiberias by diverting some tributaries in Lebanon and Syria. To prepare for defense in case of an Israeli military response to these diversions, a joint Arab force was created. The United Arab Command was composed of Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian and Lebanese elements, and was headed by Lieutenant-General Ali Amer of Egypt.

The Conflict of 1970

The partnership with the Palestinians desired by King Hussein fell apart in September, 1970. The pervasive and chaotic presence of armed Palestinian fedayeen groups who expected immunity from Jordan’s laws was leading to a state of virtual anarchy throughout the Kingdom. Moderate Palestinian leaders were unable to reign in extremist elements, who ambushed the king’s motorcade twice and perpetrated a series of spectacular hijackings. Forced to respond decisively in order to preserve his country from anarchy, King Hussein ordered the army into action.

Building Bridges East and West

Attention switched from the Arab-Israeli conflict to the Arabian Gulf in 1980 when war erupted between Iraq and Iran. Throughout the eight-year war, Jordan, along with the United States, France and Arabian Gulf countries, supported Iraq against the threat of Iranian revolutionary expansionism. Nonetheless, Jordan always called for a peaceful settlement to the war, which, in the end, claimed around one million lives. It was during this time that trade between Jordan and Iraq began to flourish. In particular, the supply line from Jordan’s Red Sea port of Aqaba overland into Iraq assumed major strategic importance, contributing significantly to the development of the Jordanian economy. This was due in part to the disruption of political and economic ties between Syria and Iraq, as Syria allied itself with Iran and halted trade with Iraq.

Jordan’s Democratic Renaissance

In recent years, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has made remarkable progress toward establishing the basics of a pluralistic, organized political structure that can serve as a model for the region. Since Jordan resumed its commitment to parliamentary politics in 1989, a number of sweeping reforms have been adopted to ensure that the venture is placed on a solid footing. Most notable among these are the reintroduction of political parties to Parliament, the drafting of the National Charter, the expansion of press freedoms and a firm commitment to pluralism and human rights. In the words of King Hussein, Jordan’s commitment to fostering a democratic political culture is an “irreversible option.” In 1989, political reform began with parliamentary elections that were hailed internationally as among the freest ever held in the Middle East. The new parliament emerged as a political force that exercised full legislative powers. In addition, the formulation of the National Charter established the framework for organized political activity in the country. The Charter, which guarantees the protection of human rights, offers an indigenous model of democratic pluralism based on the only true guarantors of stability: public participation and collective responsibility.

The Madrid Peace Process

The early 1990s marked a watershed period in the history of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The Gulf Crisis redefined the balance of power in the Middle East, reshuffled inter-Arab relations and demonstrated once again the need to work toward a just and comprehensive regional peace. Moreover, several other factors converged during this time to produce a situation propitious for pursuing peace. The termination of the Cold War allowed the Arab-Israeli conflict to be treated as a regional problem. This, combined with the international realization that Arab-Israeli peace is necessary for regional stability, provided the spark to re-ignite a hitherto dormant peace process.The Jordan-Israel Peace Treaty was signed on October 26, 1994, at the southern border crossing of Wadi ‘Araba. The treaty guaranteed Jordan the restoration of its occupied land (approximately 380 square kilometers), and guaranteed the Kingdom an equitable share of water from the Yarmouk and Jordan rivers. Moreover, the treaty defined Jordan’s western borders clearly and conclusively for the first time, putting an end to the dangerous Zionist suggestion that “Jordan is Palestine.”